Last partial update: June 2019 - Please read disclaimer before proceeding

An overview of osteoporosis in Australia

Fractures due to bone weakening caused by osteoporosis are common, especially in women

Osteoporosis is a disease of ageing and most people will get it if they live long enough. Women at the age of 60 have a 44% chance of developing an osteoporotic fracture in the future. One in four men will have an osteoporotic fracture and one in two women. In 2012, about one million Australians had osteoporosis and 4.74 million had poor bone health. This figure is set to rise to 6.2 million by 2022.

Unfortunately 26% of those suffering with these fractures do not regain independence and remain in nursing homes for the rest of their lives.

And it's not just fractures. People over the age of 60 who have an osteoporotic fracture are twice as likely to die in the following year as someone of a similar aged person without a fracture. (In hip fractures it is three times.)

Many fractures occur without symptoms, especially spinal fractures

The spine is the most common site for osteoporotic fractures, accounting for close to half of all such fractures. About 65% occur without symptoms. (They are diagnosed by X-ray.)

Many people with osteoporosis are unaware they have the disease

Many patients suffering from fractures due to osteoporosis are unaware they have the disease as about 80% of people suffering low trauma fractures are not being investigated and treated for osteoporosis. Only about 25% of women and about 5% of men who would benefit from drug treatment for osteoporosis receive it.

Prevention of bone weakening requires lifelong vigilance

A lifelong program of healthy eating and weight bearing exercise will maintain strong bones and significantly reduce the risk of osteoporosis.

What is osteoporosis?

There is a reduced amount of bone mass in osteoporotic bone

Osteoporosis occurs when bone, which has a honeycomb-like structure, becomes more porous than normal; that is, the density of bone is less. The bone that is present is normal in structure; there is just less of it. The mineral calcium is the main constituent of bone, accounting for 67% of bone mass and, as osteoporotic bone has less bone, it also has significantly reduced calcium. This reduced bone mineral (or calcium) density makes bones weaker, especially to compressive forces, and this increases the risk of fractures. Scientifically, osteoporosis is defined as a bone mineral density (BMD) at any site in the skeleton that is 2.5 standard deviations (or 25%) below that of a well young person. Bone density is usually measured by an X-Ray technique called dual X-ray absorptiometry (DXA).

Bone are changing all the time

It is important to realize that bones do not stay the same as people age. They are living tissue that is continually changing, with new bone being added and old bone being resorbed. Part of the reason for this is that bones act as a ‘calcium storage facility’ for the body. In childhood and adolescence, more bone is added than is removed and bone mass increases, with peak bone density being reached in early adulthood. However, from about the age of 30 years, more bone is lost than is added and this means that bone mass gradually reduces from 30 years of age.

Initially, unless there is a medical problem that accelerates this process, this bone loss is slight and the amount of bone present does not change greatly until menopause in women and about 50 years of age in men.

Bone loss accelerates after women reach menopause

However, in women, this bone loss accelerates at the onset of menopause (due to the reduction in the hormone oestrogen) and it is not uncommon for women to lose 15% of their bone mass in the five years after menopause. (5% in first year after menopause, 4% in the second, 3% in the third, 2% in the fourth and 1% in the fifth.). After this time, bone loss in women resumes the slow rate that occurred prior to menopause, but can still be as high as one per cent per year. At the age of 70 the rate of bone loss can increase slightly again; to about one to two per cent per year. These percentages may sound small, but added together they mean that, but by the age of 70, some women may have lost 30% of the bone mass they had at 50 years of age. In addition, following menopause there are structural changes in the way new bone is laid down that mean that bones are generally weaker for the same density levels

Men lose less bone than women

Men do not suffer this mid-life acceleration in bone loss and they tend to lay down new bone on the outside of the bone (i.e. they have wider bones) which helps bone strength. Also, they often have a 10% higher peak bone density to start with. Thus, they are less prone to suffer from osteoporotic fractures.

These facts help explain why men only suffer about 30% of all hip fractures and 20% of all spinal fractures. The other contributing factor is that they die on average about 6 years earlier than women. Improvements in health will lead to men living longer and it is thought that this increase in longevity will result in the number of males suffering hip fractures doubling over the next 20 years. (A similar increase will also occur in women as their longevity increases.)

Reduced bone density (i.e. calcium loss from bones) is a normal part of ageing

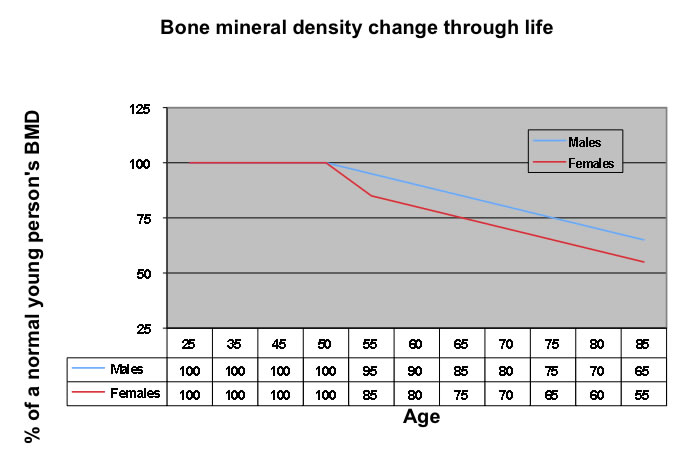

From the above it can be seen that bone (calcium) loss is a normal, although unfortunate, process that occurs with ageing and will lead to osteopororosis in many people. The figure below shows the bone loss that occurs in untreated males and females with age and indicates the likely age that osteoporosis will occur; 65 years in untreated women and 75 years in untreated men. Appropriate diet and exercise will help minimize the problem and can help reverse some of this bone loss. (It is important to emphasise that adequately exercising prior to menopause is likely to result in a higher BMD than the average woman at menopause. i.e. the woman will be starting above the 100% line on the graph below. Keeping up the exercise will hopefully ensure staying above the ‘average line’ and delay, if not prevent altogether, the onset of osteoporosis.) However, even with close attention to diet and exercise, people cannot assume that they will definitely prevent osteoporosis occurring and many women (and men) will suffer the fractures that result from this problem unless they receive treatment with medication.

Osteoporotic fractures are common

As a general guide, the risk of fractures doubles with each ten per cent loss of bone mass and tends to increase exponentially with age, especially after age 70 years.

It is important to note that many osteoporotic fractures occur in people with only moderate bone loss; say with a BMD of negative 1.8. For this reason preventative treatments need to be stated early in the disease process as waiting till the person has a BMD of negative 2.5 may be too late in many cases.

Approximately 50% of women over 60 years of age will also experience a fracture due to osteoporosis during their lifetime. In men over 60 years, approximately 30% will also experience a fracture due to osteoporosis during their lifetime. However, due to lack of awareness of osteoporosis as a causal factor, as few as 5% of these men receive treatment for their osteoporosis. For this reason, any male over 50 who has a fracture with minimal trauma should be investigated for osteoporosis.

Male osteoporotic fractures are commonly due to an underlying medical problem

Underlying medical causes for the osteoporosis are more common in men. In women, most fractures are due to ‘natural’ bone loss. However, in 60% of males with a fracture due to osteoporosis, there is an underlying medical cause, the following being the most common.

- Male hormone abnormalities

- Excess alcohol intake

- Chronic diseases, especially bowel disease that interferes with calcium absorption.

- The use of prescribed steroid medications.

- Factors that increase the risk of falls such as sleep disturbance, impaired mental status, previous stroke, senile dementia

Osteoporosis risk factors

Numerous factors cause an increased risk of osteoporosis.

The most important risk factors

- Menopause in women, especially if it occurs relatively early, around 45 years of age or before.

- Sustaining a fracture after 40 years of age

- It is important to investigate for osteoporosis to exclude it as an underlying cause of any fracture occurring in a person over 50 years of age, especially if it occurred with minimal trauma, and to look for evidence of asymptomatic osteoporotic spinal fractures.

- People who have suffered an osteoporotic fracture are at a much higher risk of further fractures.

- Spinal fractures are the most common osteoporotic fracture and often go unnoticed. A reduction in height of greater than 3cm from the height reached in early adulthood is a marker of likely spinal fractures and it is worthwhile measuring height regularly in from age 50. The appearance of a curvature in the thoracic spine (a hump-like appearance) also indicates spinal fractures have probably occurred.

- Family history of osteoporosis or likely osteoporotic fractures is a very strong risk factor

- Smoking (It increases the likelihood of sustaining vertebral fractures by 13% and hip fractures by 31%.)

- Low bodyweight, especially with eating disorders such as anorexia. This can also occur in people who over-exercise, such as elite athletes.

- Age

Other important risk factors

- Low calcium intake and vitamin D deficiency

- Lack of exercise (Unfortunately trials have not shown a reduction in fracture rate in people with osteoporosis who increase their exercise level; although it does slightly improve bone mass. Part of the reason for this may be that poorly planned exercise programmes actually cause occasional fractures. Thus, it is important that the exercise undertaken is well planned. See later.)

- Immobilisation (People confined to wheel chairs or bed.) Forty percent of all hip fractures occur in people in aged care facilities.

- Regular, excessive alcohol consumption (especially in men)

- Predisposing medical conditions, including conditions causing excess glucocorticoid secretion, chronic kidney or liver disease, Turner’s syndrome, male hypogonadism, thyroxine excess, rheumatoid disorders, bowel malabsorbtion disorders such as coeliac disease, primary hyperparathyroidism, anyone who has had an organ or bone marrow transplant, multiple myeloma.

- Medications. An important cause of osteoporosis is prolonged use of medical steroid therapy. All people, male or female, on more than 7.5 mg per day of the drug prednisone or 2000mg per day of beclomethasone (a steroid spray used for asthma) for three months or more should be investigated for osteoporosis. Excess thyroxine, some epilepsy medications (especially phenytoin), selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs - used for depression / anxiety), anti-oestrogens and anti-androgens, and loop diuretics such as frusemide (Lasix) also cause increased bone resorption. (A calcium retaining thiazide diuretic would be a better choice that frusemide.)

- Sedentary lifestyle over many years.

- Those with a high risk of falls or who have had falls already. Factors influencing this risk include:

- poor eyesight

- poor balance or poor lower limb muscle strength

- the use of multiple medications

- the use of medications that affect alertness, especially sedatives and medications for depression

- age

- impaired cognition

For women, it is important that the above risk factors are considered before as well as at menopause as they need to be identified and avoided or treated as early as possible.

Determining your risk of osteoporosis.

A person's overall risk of osteoporosis can be assessed using either:

- the World Health Organisation's risk assessment tool. It can be found at: http://www.shef.ac.uk/FRAX/tool.jsp

- The Garvan Institute bone fracture risk calculator; available at: http://garvan.org.au/promotions/bone-fracture-risk/calculator/

Diagnosing osteoporosis

People who need investigation for osteoporosis

Osteoporosis is diagnosed by measuring a person’s bone mineral density (BMD). It is not an investigation that is routinely done but is recommended for the following people.

- Anyone who has had a fragility (low-level trauma) fracture. This is a fracture that would not be expected to occur if similar trauma was suffered by a well young adult. (Unfortunately, most people who are operated on for a fracture are not subsequently assessed for underlying osteoporosis.)

- All person over the age of 70

- Any person over 50 years of age who has any of the following

major risk factors

- Rheumatoid arthritis

- Thyroid disease

- Chronic kidney or liver disease

- Coeliac disease / metabolism disorders

- Premature menopause

- Hypogonadism

- taking gglucocorticord (steroid) therapy for over 3 months

- Anti-androgen therapy

- Anyone with the predisposing medical conditions listed above in the risk factor section

Testing well women for osteoporosis; is it worthwhile?

Even without the presence of increased risk, some women may choose, quite reasonably, to have their bone density measured around menopause as a precaution. After menopause bone loss will accelerate rapidly and any existing osteoporosis is best diagnosed before this time so that preventative measures can be taken to minimise further loss. BMD is only eligible for a Medicare rebate in a few circumstances, such as when an osteoporotic fracture is present. Women will need to check with heir GP as to whether they fall into one of these categories. Women choosing to have BMD done as a precaution have to pay all the costs involved.

How is bone mineral density testing done?

The most common and best method of measuring BMD is dual-energy X-Ray absorptiometry (DXA). (It takes about 20 minutes, involves minimal radiation exposure (much less than a chest Xray).

The measurement of BMD at any site in the body is a good predictor of the bone density at all sites in the body. Initial assessment is usually done at the femoral neck (the hip). (The proximal femur and lumbar spine are also sometimes used; very occasionally, the wrist.) Those taken at the proximal femur (the part of the long bone in the upper leg that is adjacent to and part of the hip joint) are the best predictor of fracture risk (especially hip fracture risk) and are more reliable as they are less likely to be influenced by osteoarthritis changes than the spine.

An individual’s BMD is assessed by comparison with the BMD for a healthy young adult (of the same sex and ethnicity) and is expressed in terms of the ‘T score’. The ‘T score’ of a healthy young adult is given the value zero and BMD is expressed as standard deviations above or below zero. Each unit of standard deviation equals a 10% change from the ‘normal young adult’ score. For example, a ‘T score’ of negative one indicates the person has a bone density 10% below the average for a healthy young adult. As a general rule, the risk of fracture doubles with each standard deviation below zero i.e. a person with a ‘T score’ of negative one has twice the risk of having a bone fracture due to bone loss as healthy young adult. A ‘T score’ of negative three indicates a BMD 30% below the ‘young adult average’ and increases the risk of fracture to eight times (i.e. 2 x 2 x 2 = 8) that of a healthy young adult.

Osteoporosis is defined as having a ‘T score’ of negative 2.5 or less. This is even more significant (i.e. severe) if a minimal traume fracture has already occurred.

Typically the 'T score' drops about 0.1% per year as people age. Thus, a person with a 'T score' of -1.5 could be expected to have a 'T score of -2.5 in ten years time.

Bone density scoring |

|||

‘T’ Score |

Occurrence in Australians 60 yrs and over |

Risk of fracture due to osteoporosis |

|

|

Females |

Males |

|

A positive score |

|

|

Above normal bone mineral density and a risk of fractures below that of a normal young adult of the same gender. |

Zero |

|

|

The same level of fracture risk as that of a normal young adult of the same gender. |

Negative 1.0 to negative 2.5 (i.e. 1.0 to 2.5 standard deviations below normal) |

51% |

42% |

Osteopenia present

A bone density 10% to 25 % below that of a young normal adult of the same gender.

A mildly increased risk of fracture. |

Less than negative 2.5 (i.e. over 2.5 standard deviations below normal) |

27% |

11% |

Osteoporosis present.

A bone density more than 25 % below that of a young normal adult of the same gender.

A significantly increased risk of fractures. |

BMD is also sometimes expressed as the ‘Z score’. Here, instead of comparing the person’s result with the normal reading for a normal young adult, the result is compared with the BMD value for a normal person of the same age. Thus, the ’Z’ score gives an indication of how a person’s BMD compares with the normal for their age group. If the ‘Z score’ is less than negative one and a half (i.e. more than 15% below the normal for healthy person of the same age), it is an indication that, in addition to bone loss from normal ageing, there is quite likely to be an additional medical problem causing bone loss. This person requires investigation to determine the nature of the underlying problem.

How often should BMD testing be done?

As bone density usually falls at no more than one to two per cent per year in older people, testing is not needed more often than second yearly. A few specific groups of people are likely to suffer quicker bone loss, e.g. those on prolonged high doses of corticosteroids and these people may need more frequent testing.

Bone ultrasound testing

While bone ultrasound testing done with good equipment and a competent operator is also reliable in determining bone density and in predicting the likelihood of future fractures, X-ray is still the preferred investigation. Ultrasound heel testing, usually offered in shopping centers, is less accurate and any positive test needs to be repeated with a proper X-ray. Ultrasound testing can sometimes give false positive and false negative tests; that is, it indicates that some people without osteoporosis have the problem and visa versa.

How good is BMD testing at predicting fracture occurrence?

About 50% of minimal trauma fractures occur in people with T-scores above -2.5 (i.e. in the normal or osteopenia category.) Thus, other risk factors need to be considered also.

Measurement of Absolute Fracture Risk

Two good tools for measuring Absolute fracture risk are

- The Garvan Fracture Risk Calculator www.garvan.org.au/bone-fracture-risk

- The Fracture Risk Assessment Tool https://www.sheffield.ac.uk/FRAX/tool.aspx?country=31

Prevention and treatment of osteoporosis

Most women and men feel that lifestyle measures, including diet and exercise, will provide adequate protection against osteoporosis. Unfortunately, as figure 27 shows, this is not always the case and many will need to use medication as well. Prevention can be divided into four areas which are dealt with fully below.

1. Lifestyle modification (exercise and diet). As stated previously, lifestyle measures should be initiated early in the disease as many fractures occur before overt osteoporosis has developed.

2. Treating any underlying medical causes of osteoporosis (including prescribed medications)

3. Using medications that will slow or reverse bone loss

4. Fall prevention measures.

1. Lifestyle measures

Successful prevention of osteoporosis relies on attaining maximum calcium levels in childhood and minimizing loss during adult life. The lifestyle factors that contribute to maximizing BMD are as follows.

- Maintaining an adequate calcium intake throughout life. This is particularly important as recent evidence is suggesting that increasing calcium intake later in life does not reduce fracture risk in those at incressed risk of osteoporosis.

- Maintaining adequate vitamin D levels throughout life through adequate sun exposure and diet.

- Maintaining adequate exercise, especially weight-bearing exercise, throughout life to:

- maximize peak bone mass when young (early twenties in women)

- maintain bone calcium levels at the highest possible level with ageing

- help maintain adequate levels of balance, fitness and agility to reduce the risk of falling.

- Reducing routine alcohol consumption to a maximum of two drinks per day (the maximum intake to maintain optimum health). Alcohol increases bone resorption and can reduce calcium absorption from the bowel.

- Ceasing tobacco use, as smoking increases bone resorption.

Adequate calcium intake

About 75% of Australian women and fifty percent of Australian men have calcium intakes less than that recommended by the National Health and Medical Research Council and around 15% of women have a severely low intake level of less than 300mg per day.

Importantly, the rate is highest in the groupgs that need calcium the most, adolescent girls and postmenopausal women, with 90% of both groups having an inadequate intake.

The amount of calcium absorbed from the diet decreases with age and thus dietary intake needs to increase with age. (About 60% of dietary calcium is absorbed from the gut by infants whereas only about 20% is absorbed by adults. The rest is lost in the feces)

Calcium intake is important in building and maintaining bone density. Establishing a high peak bone density, which occurs in early adulthood, can prevent later fractures, as can reducing the rate of decline in bone density throughout adult life; and especially postmenopause. Roughly 50% of peak bone mass is accumulated in the period from puberty to early adult life and it is during this time that maintaining adequate calcium intake is vitally important. The rapid increase in height that occurs during puberty can make bones weak temporarily and calcium intake is important in reduce the risk of fractures during this time also. Maintaining adeqate calcium intake during adult life slows down the reduction in bone density that naturally occurs and is especially important for women after menopause. Unfortunately research has not shown that increasing calcium intake reduces fracture rates once osteoporosis has become established, except perhaps for a slight reduction in vertebral fractures. For this reason increasing calcium is a weak-rated intervention for osteoporosis. When combined with vitamin D supplements in people in institutional care, the benefits are greater with a 13% decrease in the fracture rate.

Thus, it is vital to maintain calcium intake throughout childhhod and adult life to help prevent osteoporosis occurring.

The accompanying table shows the recommended calcium intake for men and women.

| Advised calcium intake | ||

Recommended dietary intake |

||

Calcium (in mg per day)* |

Dairy food (in serves of dairy food per day)** |

|

Males |

||

Boys 2 to 3 years |

500 |

1.5 serves |

Boys 3 to 8 years |

700 |

2.0 serves |

Boys 9 to 11 years |

1000 |

2.5 serves |

Boys 12 to 18 years |

1300 |

3.5 serves |

Men 19 to 69 years |

1000 |

2.5 serves |

Men 70 years and over |

1300 |

3.5 serves |

Females |

||

Girls 2 to 3 years |

500 |

1.5 serves |

Girls 3 to 8 years |

700 |

1.5 serves |

Girls 9 to 11 years |

1000 |

3.0 serves |

Girls 12 to 18 years |

1300 |

3.5 serves |

Females 18 to menopause |

1000 |

2.5 serves |

Menopause to 69 years |

1300 |

4.0 serves |

Women 70 years and over |

1300 |

4.0 serves |

Females - Pregnant / lactating |

||

14 to 18 |

1300 |

3.0 serves |

19 to 50 |

1000 |

2.5 serves |

| Maximum intake for all people – 2500mg per day. | ||

* The estimated average requirement is the amount of calcium that an average person requires. It is calculated for a 76kg man and a 61kg woman. (Larger people would need more and smaller less.) The recommended dietary intake is the amount that would provide enough calcium for almost all the population. (EAR + 2 standard deviations = RDI) ** A serve is 250mL of milk, 40g of cheese, 200g of yoghurt or 120g of ricotta, 250mL of soy or other cereal drink that has been fortified with at least 100g calcium per 100mL of beverage |

||

| Source: NHMRC Publication: Nutrient Reference Values for Australia and New Zealand | ||

Those at most risk of having an inadequate calcium intake are the following.

- The elderly (Calcium absoption from the bowel decreases with age and this is often made worse by low vitamin D levels in this age group. Also, most elderly people have reduced food intake compared with younger adults and this makes achieving an intake of 1300mg of calcium through diet alone difficult.)

- Socially isolated people

- Post-menopausal women (Reduced sex hormone levels in post-menopausal women deceases calcium absorption from the bowel.)

- Other women with sex hormone deficiency

- People taking steroid medication

- People with intestinal disease. (Such disease disrupts calcium absorption)

- Growing children. Childhood is the most important time during life for increasing bone stores and adequate calcium intake and exercise during this time are vital in achieving maximum adult bone mass / strength. (The bone tissue stored by a girl from age 11 to 13 equals the amount that is lost in the 30 years following menopause.)

Food sources of calcium

Dairy products: As well as being the best source of dietary calcium, dairy products also provide calcium that is the most easily absorbed from the intestine; and very importantly, it includes many other important nutrients such as protein, phosphorus, magnesium, zinc, iodine, iron and vitamins, to name just a few. To achieve adequate calcium intake from diet alone, most people need diary products of some sort. The best way to achieve this is with at least two (three in the elderly) serves of calcium enriched foods per day; good choices are a 250 ml glass of calcium enriched low-fat milk or a serving of calcium enriched low-fat yoghurt, both of which provide about 400 mg of calcium. There are also other calcium fortified beverages including soy, almond milk, orange juice based products. Using reduced fat cheeses as a daily calcium source is a less desirable choice as they still have a relatively high fat content and much of this is saturated fat. Soy products with added calcium are a good alternative for people who can’t have diary products.

A good way of getting enough dairy is to have a serve of dairy with beakfast and evening meals every day.

Other advantages of consuming dairy productsEvidence with a probable association between consuming milk, cheese and yoghurt and other health benefits include:

|

Other good foods sources of calcium (mg of calcium in serve): Tofu (310mg in 1/2 a cup), almonds (180mg in80g of nuts), canned salmon (180mg per 80g salmon), soy beans (76mg in 100g of beans), wholemeal bread (30mg per slice), oranges (33mg per orange), broccoli (27mg in half a cup), spinach (20mg in one cup).

Some foods affect calcium absorption

Calcium absorption from the intestine and loss from the body can be affected by the foods eaten.

- Substances that can decrease absorption include tannins in tea, iron, caffeine, excess alcohol, the phosphate in soft drinks, and phylates that are present in fibre. High protein diets, a low vitamin D level and smoking can also reduce levels.

- Tablets containing calcium carbonate are best absorbed in an acidic stomach environment and thus should be taken with food. (They do however interfere with iron absorption from the diet.) Tablets containing calcium lactate, citrate and gluconate can be taken at any time.

- A diet high in sodium (salt), caffeine or protein foods can increase calcium loss via the kidneys / urine and thus reduce body calcium stores.

An adequate vitamin D level assists in calcium absorption.

Calcium supplements - Currently they are NOT recommended for most people

At present there is considerable debate regarding the potential benefits that taking calcium supplements provides with regard to reducing fracrtures and some experts feel that any benefit is negated by the side effects of taking this medication. One of the problems in medicine is that, not uncommonly, therapies that seem to make sense do not translate into providing benefit. and this is probably one of those instances. Taking calcium should increase bone density and this should reduce fracture incidence but research to date has not really found this to be the case. Thus, as calcium supplements also have side effects, for most people an adequate calcium intake should be sourced through the diet. The main exception is the use of calcium supplements in elderly people in institutions. (In these people supplements should be given with vitamin D supplements.)

Cardiovacular disease risk and the safe use of calcium supplements: Post-menopausal women and older men require 1000mg to 1300mg of calcium per day and many find this difficult to achieve from diet. In the past calcium supplements have been routinely recommended for these people. Recently however, some evidence has emerged that calcium supplements increase the risk of cardiovascular disease (heart attacks) and the use of calcium supplements has been brought into question. At the present there is still considerable controversy about the actual cardiovadcular risk associated with calcium supplement use and thus it is currently recommended that while this is being sorted out, people should try whererever possible to gain their required calcium intake from their diet. (The fact that taking calcium supplements has been shown to only produce a slight reduction in fracture rates makes this recommendation even more sensible.)

Advice regarding calcium supplement use is likely to change regularly over the next few years as more evidence regarding its safe use becomes available and people who can’t get adequate calcium from their diet will need to discuss with their doctor whether supplements are a safe option for them. (It will depend on their rsik of both fractures and cardiovascular disease.)

Recommended doses of calcium supplements: While supplements are not recommended for the general population, there will be occasional cases where they are thought necessary and recommended by doctors. The recommended supplement dose is that required to achieve a daily calcium intake of 1000mg to 1300mg per day. Some of this will be achieved by diet (often around half) and thus usually only about 500mg of supplements need to be taken daily. The main side effect of calcium supplements is constipation. (Flatulance and bloating also sometimes occur.) The use of supplements can provide a mild to modest reduction the risk of fracture; in the order of 15%. While this is very beneficial for all people, it is not an adequate fracture risk reduction for someone with established osteoporosis and they will generally require additional medication to further reduce their risk. (Those taking oral bisphosphonates for osteoporosis (see later) need to remember that this medication needs to be taken several hours apart from calcium supplements, otherwise the two medications interfere the each other’s absorption.)

When using calcium supplements, be careful not to confuse the weight of the calcium contained in each tablet with the total weight of calcium carbonate in each tablet. It is the weight of the calcium that is impotant. Depending on the tablet, this can vary from 20 to 600mg of calcium per tablet. Therefore, check when purchasing or when a doctor prescribes calcium tablets.

Inadequate vitamin D intake

Vitamin D is needed for the body to be able to absorb dietary calcium from the bowel and helps with calcium deposition into bone. The incidence of vitamin D deficiency in Australia is much greater than was previously thought, with up to 10% to 20% of the ‘normal’ population being vitamin D deficient. This occurs more commonly in winter as the main source of vitamin D in Australians is from the skin (and its production requires skin exposure to sunlight). However, there is considerable individual variation that is to an extent genetically determined and thus vitamin D deficiency is difficult to predict. Also, people with dark skin do not produce as much vitamin D in their skin.

Vitamin D deficiency is a problem because it increases the risk of osteoporosis developing and, at very low levels (less than 25nmol/L), it can also cause osteomalacia in adults. (This condition is associated with bone weakness, bone pain and muscle weakness and is due to new bone not mineralising i.e. calcium does not deposit in the new bone. It is also caused by very low calcium levels.) Other conditions associated with low vitamin D include muscle weakness, rickets in children and an increased risk of falls / fracture. It is also linked to an increased risk of type 2 diabetes and diabetes in pregnancy. The reason for this association is not known at present.

Food does not supply adequate amount of vitamin D in Australia

Vitamin D is found in small quantities in oily fish (e.g. salmon), eggs and milk products and some foods are fortified with vitamin D, including some types of margarine and milk. The recommended daily intake of vitamin D is 400 to 800IU (10 to 20 micrograms) per day. However, in Australia, it is quite difficult to get adequate amounts of vitamin D from diet alone. (Some other countries, especially those in northern Europe, fortify foods with vitamin D.)

Sunlight is the best source of vitamin D in Australia

By far the best way to source the required vitamin D intake is by exposure to UVB radiation from sunlight, which converts a vitamin D precursor (7-dehydrocholesterol) to vitamin D in the skin.

The amount of sunlight exposure required to produce adequate vitamin D depends on the amount of skin exposed, skin colour, and the intensity of the sunlight, which varies according to the latitude, the time of year and the time of day, and cloud cover. It is unfortunate that UVB radiation is also responsible for sunburn and skin cancers, which are a huge health problem in Australia and for this reason it is important to avoid excessive sunlight exposure. Luckily, adequate vitamin D production in the skin requires small amounts of sun exposure with exposure of about 15% of the skin to a very modest amount of sunlight being adequate. This equates to about 33% of the sunlight (i.e. UVB radiation) which would cause even the faintest redness in the skin. The table below gives the recommended guidelines regarding the sun exposure required to produce adequate vitamin D. As mentioned in the table, people with dark coloured skin need a sunlight exposure that is three to four times greater than those mentioned to create the required amount of vitamin D. Older people also need slightly longer exposure than that mentioned in the table.

An important point to note is that glass filters out the radiation that creates vitamin D in the skin and thus sun exposure behind a window is not helpful. (This is important in people in institutional care.)

Recommended daily sun exposure for people with moderately fair skin* (in minutes per day) |

|||

Location |

December at 10am or 2pm** |

July at 10am or 2pm |

July at noon |

Cairns |

6 to 7 |

9 to 13 |

7 |

Brisbane |

6 to 7 |

15 to 19 |

11 |

Perth |

5 to 6 |

20 to 28 |

15 |

Sydney |

6 to 8 |

26 to 28 |

16 |

Adelaide |

5 to 7 |

25 to 38 |

19 |

Melbourne |

6 to 8 |

32 to 52 |

25 |

Hobart |

7 to 9 |

40 to 47 |

29 |

Auckland |

6 to 8 |

30 to 47 |

24 |

Christchurch |

6 to 9 |

49 to 97 |

29 |

*Only about 15% of skin area needs to be exposed, which is equivalent to the legs or the face, hands and arms. Exposure times for those with highly pigmented skin will need to be 3 to 4 times greater. |

|||

** 1 pm and 3pm for locations that have ‘daylight saving months’. |

|||

To avoid skin damage, sun exposure should occur before 10am or after 3pm and not exceed the recommended duration. Additional exposure gives NO added benefit. |

|||

Who is most at risk of having vitamin D deficiency?

Those at most risk of having an inadequate vitamin D levels are the following.

- The house-bound elderly or those in institutions. (One study found an incidence of over 75% in northern Sydney.) (These people usually require calcium and vitamin D supplements.)

- Other elderly people, especially those iiving incolder climates. (The incidence is about 45% in people over the of 50 years living in Tasmania.)

- People with dark skin

- People who have limited sunlight exposure due to covering most of their skin with clothes; for example, Islamic women who wear the hejab. This is especially of concern when the woman is of child bearing age as a low vitamin D level during pregnancy may be associated with infant rickets.

- Pregnant women

- The breastfed infants of pregnant women who are dark skinned or whose clothing covers most of their skin. These infants may need vitamin D supplements for the first 12 months of life.

- People on certain medications (e.g. some anti-epileptic medications)

- People with cognitive impairment

- People with malabsorption due to gastrointestinal disease

Screening for people at risk of vitamin D deficiency

While screening is not generally recommended for vitamin D defiviency, it is probably wise to recommend testing in those at high risk. (See list above.)

Testing for vitamin D

Testing for Vitamin D levels in the blood is difficult and some types of tests are not very reliable. It is important to make sure your doctor is confident that the pathologist he / she uses has reliable testing procedures in place. (This means having asked the pathologist that this is the case.)

Classification of vitamin D blood levels, when the sample is taken at the end of winter or in eaerly spring, are as follows:

- Optimum blood level - greater than 50nmol/L

- Mld deficiency - 30 to 50nmol/L

- Moderate deficiency - 12.5 to 30nmol/L

- Severe deficiency - less than 12.5nmol/L a severe deficiency.

Levels are highest at the end of summer and lowest at the end of winter, with the difference commonly being about 20 to 35nmol/L. It is thus critical to take into account the time of year a vitamin D test was done when assessing its significance. For example, a mild deficiency is much more significant if it occurs at the end of summer than the end of winter.

Vitamin D supplements

Supplements are recommended for those at high risk of vitamin D deficiency (see list above); especially if a blood test for vitamin D has shown inadequate levels. The usual dose is about 800IU (20 micrograms) per day or monthly treatments of 24,000IU.

Past research has shown that Vitamin D supplements can reduce the risk of falls but more recent studies have cast some doubt on this. Monthly treatments seem to offer the best results but further research needs to be done.

Exercise and osteoporosis prevention

It is vitally important for everyone (but especially women) to do regular weight bearing / high impact exercise in their adolescence and early adulthood as this will assist in achieving the highest maximum BMD possible for that person. The rate of bone loss is the same irrespective of the person’s starting BMD. Thus, a person with a higher peak BMD in their young adult life (and thus stronger bones) will maintain this advantage as they get older and will thus always have stronger bones than someone who had a lower peak BMD in their young adult life.

The type of exercise done does depend on age and whether oseoporosis / other illnesses are present. All exercise programs should be commenced gradually and under supervision of a qualified trainer to avoid injury and older people / people with existing illness need medical assessment before starting.

Exercise in young people without osteoporosis

Daily exercise is necessary if adults are to keep their bones strong and it also aids in the prevention of injury. To be beneficial, ‘osteoporosis prevention exercise needs to be done regularly, at least three times a week, every week throughout life. The benefits of exercise quickly reverse once exercise is ceased. Generally speaking, exercise is more beneficial for bone strength if it is done fairly vigorously and in short bursts. Unfortunately not all people can exercise vigorously and it must be remembered that all exercise is beneficial for bone strength. It also needs to be stressed that improving balance and co-ordination are very important in reducing fall and fracture risk and these benefits improve also with any exercise.

Only the bones that are placed under stress during exercise benefit, so it is very important to perform a wide variety of exercises that affect the bones in the arms, legs and trunk as all are common sites of osteoporotic fractures. There are two main types of exercise that are beneficial for improving bone strength; weight-bearing exercise and strengthening (resistance) exercise.

The best type of exercise is weight bearing, high-impact exercise, especially exercises that distribute these forces around the body. Exercises that involve jumping activities are best. Weight bearing exercise involves exercising whilst in an upright position, allowing gravity to have an effect. It includes:

- Walking

- Normal walking is not particularly effective at increasing bone density. Brisk walking is better but overall, people really need to progress beyond walking to higher impact activity to gain significant obone density benefit. (It needs to be stressed that walking is good exercise for cardiovascular illness prevention and is always better than nothing.)

- Jogging / running

- Jumping exercises

- Netball

- Gymnastics

- Tennis

- Dancing

- Golf

- Lifting weights

As stated above, it is important to vary the type of high impact exercise so that forces are applied to bones in different directions and thus a variety of high-impact exercises should be part of each person's daily exercise routine. Basing exercise programmes on just one exercise, such as running, is less helpful. (Running is helpful as it provides moderate impact but the body does get used to it and its repeditive nature leads to uneven gains in bone strength. Other activities need to be incorporated as well.)

Resistance or strength training usually involves using weights on the arms and legs while doing an exercise routine and can be done on land or in the water. Gradually increasing the size of the weights used will increase the benefit. One to three sets per day of eight to twelve repetitions at least three times a week are recommended. Balance and coordination exercises are always beneficial for any age group and, for younger people, high-impact sports that involve activities such as jumping are also advantageous. Arthritis and the risk of injury makes participation in high impact sports difficult as people age and such activities are replaced by resistance exercises in this age group. (See below.)

Introduce exercise programmes gradually: To avoid injury, all exercise programs need to be introduced gradually and a consultation with a general practitioner is recommended before starting, especially when the person is over 40, has an existing medical problem, or has not been exercising regularly.

Exercise in people with osteoporosis and in older people

People with osteoporosis are at increased risk of injury from exercising and should definitely consult their GP before starting. The risk of exercising actually causing a fracture means that certain exercise limitations and precautions are needed. These often include:

- avoiding jarring, high impact, twisting or abrupt / sudden movements.

- avoiding abdominal curl-up type exercises.

- avoiding forward bending from the waist, especially if carrying any weight

- avoiding heavy lifting.

- avoiding exercises that significantly increase the risk of falling

Weight bearing exercise may also not be appropriate for women with established osteoporosis.

Unfortunately these are just the sort of exercises that provide benefit with regard to the prevention of developing further osteoporosis.

In people with osteoporosis, it is more appropriate to aim at achieving improved muscle strength, coordination, and balance and stability, as all these attributes can help prevent falls. A strengthening exercise program and a falls prevention program are best at achieving these aims. Water exercises may be of benefit for frail people or in those recovering from a fracture. Tai Chi is also advocated for some people.

People with osteoporosis should have an individual program designed for them by a physiotherapist. Their supervision can also help reduce the risk of falls and they can give advice regarding the relief of acute and chronic pain associated with osteoporosis.

Fall prevention is an important area of health prevention in the elderly generally, and especially in those with osteoporosis and is covered in detail in this book. Also, special pads can be worn to protect the hips. These pads reduce the risk of hip fractures from falls by about 50%.

How much exercise

Exercises should be introduced gradually until about 30 to 40 minute a day, four days a week (at least) is achieved. This does not have to be done continuously. It can be broken up into several smaller amounts during the day and in fact the benefit is greater if exercise is split up in this way. Pain is usually a sign of over exercising or that something is wrong and a consult with a doctor is required if this occurs.

Over-exercising

Finally, over-exercising can be as bad as under-exercising. Young female athletes and dancers are two groups likely to over-exercise. People should not allow exercise to reduce their weight below a body mass index of 20 and women should definitely not allow it to affect their menstrual periods, as this will actually cause bone loss, not gain. Women who start to develop changes in their menstrual pattern (periods) following weight loss should consult their doctor, especially if they stop menstruating.

2. Adjusting medication that exacerbates osteoporosis

Several medications can exacerbate osteoporosis and should be avoided where possible in elderly people or those with established osteoporosis. These are mentioned in the section on causes of osteoporosis. Drugs that increase the risk of falls should also be ceased where possible. (See fall prevention section.)

People on prolonged treatment with corticosteroids have a 30% to 50% risk of an osteoporotic fracture and should be offered medication to help prevent osteoporosis. (See below.)

3. Medication for osteoporosis

Despite adequately addressing osteoporotic risk factors and lifestyle issues (including maintaining adequate calcium intake and vitamin D levels), many older Australians need medication to help reduce their bone loss and thus reduce their risk of fracture. Luckily, available therapies can reduce this risk by about 50% within a year of beginning treatment. These medications are used to treat rather than prevent osteoporosis. People need to discuss these medications in detail with a doctor prior to commencing treatment (if needed). A guide to who should be treated appears in the table below.

Guide to therapy for osteoporosis |

||

T-score |

Past fragility* (osteoporotic) fracture |

Therapy |

Greater than negative 1.0 |

Absent |

Reassure & follow up in 2 years |

Negative 1.0 to negative 2.5 |

Absent |

Assessment by doctor. Exclude medical causes for osteoporosis. Advise regarding reducing osteoporosis risk factors, diet, exercise, other lifestyle concerns. (May require occupational therapist physiotherapist, dietitian etc) Follow up regularly. |

Negative 1.0 to negative 2.5 |

Present |

Above plus treat with medication. |

Less than negative 2.5 |

Absent or present |

Above plus treat with medication. (Medication in this group reduces future fracture risk by 30% to 60%.) |

* A fragility fracture is one that occurs with minimal trauma and implies that the fracture would not have occurred if similar trauma had been incurred by a normal young adult. (This includes most vertebral fractures.) |

||

It is important to recognise that medication can only assist in preventing future fractures, achieving reductions in future fracture risk of about 50%. It also can not reverse existing damage caused by past fractures.

There are two significant problems with the adequate provision of medication to prevent osteoporosis.

- Firstly, only about 20% of women with post-menopausal osteoporotic fractures are being treated with medication. (The same applies for men with osteoporosis.)

- Secondly, compliance in taking medication for osteoporosis is poor, as is often the case with preventative medications that need to be taken for the long-term. Only about 33% of patients remain on treatment 12 months after commencement and thus few obtain significant benefit.

First line medications for osteoporosis

Bisphosphonates:

Bisphosphonates are effective first-line therapies for reducing the risk of all fractures, including vertebral and hip fractures, in people with a past history of fractures. (They have been shown to reduce vertebral fractures in post-menopausal women by 50%, with their effect on fracture rates occurring within about 12 months of use. They act by reducing bone breakdown and thus increase bone density (by about two to four percent in the spine and 4% to 8% in the hip after several years of treatment).

With regard to preventing fractures in people with no past history of fractures (i.e. primary prevention), only the bisphosphonate alendronate has shown to be of benefit; and then only in reducing vertebral fractures. Thus, they are for the treatment of established osteoporosis (especially those with a past history of fractures), not for the prevention of osteoporosis developing.

Their side effects include nausea, heartburn, reflux, stomach pains and occasionally oesophageal ulceration. They need to be taken on an empty stomach (usually first thing in the morning) as they are not well absorbed and, to reduce the incidence of gastrointestinal side effects, bisphosphonates should be taken with a full glass of water and the person then needs to sit or stand upright for 30 minutes following taking the medication. They should also not be taken with calcium supplements as the calcium can reduce bisphosphonate absorption. They are usually taken once per week. Evidence regarding the effects of long-term use of bisphosphonates is lacking and thus most doctors only recommend staying on the medication until BMD has improved; usually several years and no more than five to seven years. If studies in progress provide evidence proving the safety of long-term use, this restricted treatment period may be extended.

The two in common use at present are risedronate (Actonel) and alendronate (Fosamax)

Denosumab

Denosumab is a monoclonal antibody and is administered by 6-monthly subcutaneous inkections.

Raloxifene:

Raloxifene is a selective oestrogen receptor modulator and acts by increasing BMD in the same way as the hormone oestrogen does. It plays a small role in the secondary prevention of osteoporosis in post-menopausal women where prevention of vertebral fractures is the aim. (Bisphosphonates are better at reducing non-vertebral fracture risk.) There is a possibility that it may increase cardiovascular morbidity and mortality as it affects oestrogen receptors. It may increase the risk of venous thrombosis (DVTs or clots in the legs) and should be stopped if the person needs to spend a prolonged period immobilized. It should not be prescribed to a woman who has an increased risk of clotting. In the breast it acts in the opposite way to oestrogen and actually decreases the risk of breast cancer developing. It may exacerbate hot flushes in women close to the menopause and it is thus best used once this symptom has subsided.

Non-first-line therapies for osteoporosis

Parathyroid hormone (PTH – teriparatide): This medication stimulates bone formation and has been shown to reduce both spinal and non-spinal fracture risk by about 60 per cent in post-menopausal women. It is used for people with osteoporosis who have had a previous fracture and in whom other medications are unsuitable.

Calcitonin: A naturally occurring hormone that increases bone density.

Fluoride

Anabolic steroids

Active vitamin D metabolites (e.g. calcitriol)

Etidronate

New therapies

Strontium ranelate (Protos): This new agent acts by reducing the rate of bone resorption and by increasing bone deposition and has been shown to reduce the risk of all types of fractures.

Ibandronate sodium (Bon Viva): This is a new bisphosphonate that needs only to be taken once a month.

Oestrogen therapy (Hormone Replacement therapy or HRT)

HRT is a most effective treatment for preventing osteoporosis in post-menopausal women and in the past has been used as a preventative treatment for osteoporosis. This benefit however requires the use of HRT for many years and recent evidence has shown that the risks associated with taking this medication long-term outweigh its benefits in reducing osteoporotic fractures. Thus, it is not often recommended as treatment for reducing fracture risk. HRT is now mostly used for the short term treatment of menopause symptoms where appropriate and the short term nature of this use means that it is unlikely to have a beneficial effect regarding osteoporosis prevention.

4. Fall prevention in adults

Fall incidence

Falls are a huge problem for elderly Australians; the ‘fall rate’ is about 20% per year for women aged 50 but increases to 33% in 65 year olds and 50% in 85 year olds. (In 85 year old men the rate is about 33%.)

While luckily only a few of these falls are serious and result in fractures, they still have very significant consequences. A fall reduces the confidence of the elderly person, making them less likely to engage in physical activity in the future. This leads to less physical competence and an increased likelihood of falling again. 50% of those who have fallen once will fall again. Falls are the sixth most common cause of death in the elderly and the most common cause of placement in nursing homes.

Fall Prevention

Preventing falls requires an overall assessment of the person and their environment by doctors, physiotherapists, occupational therapists and social workers. Physical impairments, such as low blood pressure, lower limb arthritis, gait and balance problems, and visual and hearing abnormalities, need to be assessed and, where necessary, medication adjusted.

Drugs associated with a high risk of falls include anti-hypertension medications and drugs for the treatment of mental health problems such as depression, anxiety, insomnia and schizophrenia.

The risk of falling can also be reduced by physical activity programs to improve gait and balance, and by creating a safer home environment, both internally and externally. Vitamin D deficiency causes weakness and needs to be checked for in the elderly.

People who have already had a fall or who lack confidence in their physical activity capabilities require proper assessment to help prevent them falling in the future. Assessment is also recommended when any of the following risk factors for falls or fractures exists.

- Osteoporosis

- Impaired balance, giddiness: These people need a balance and resistance exercise program.

- Significant arthritis

- Muscular weakness or walking abnormalities, such as unsteadiness. These can be caused by neurological conditions or numerous other chronic medical problems.

- Being on multiple medications (four or more)

- Impaired gait, balance problems

- Acute illness or recent hospital discharge

- Visual or hearing impairment

- Depression

- Foot pain or deformities

- Cardiac arrhythmias

- Postural hypotension. Postural hypotension is dizziness that occurs due to a fall in blood pressure that occurs when getting into an upright position. Assuming there is no correctable cause for this problem (especially medications), people who get dizzy getting out of bed need to assess how long it takes their blood pressure to adjust to an upright position. This can vary form half a minute to 10 to 20 minutes. During this time the person needs to remain seated on the edge of their bed.

Altogether, those requiring assessment include at least 25% of those over 70 years of age. However, anyone who wishes to reduce their risk of falls should seek assessment.

Physical activity and home assessment programs

Being physical active is one of the best ways to minimize the risk of falls. In women over 80, an individually tailored exercise program that incorporates muscle strengthening (resistance training), balance training and a walking plan can reduce all falls by up to 45% and falls associated with serious injury by 25%. This is especially benefits people who have had a hip fracture.

Exercise that helps build muscle strength (resistance exercise) also increases bone strength and can help reduce the pain associated with osteoporosis, including pain associated with curvature of the spine (kyphosis) that occurs due to wedge fractures of the vertebrae.

It is important that a physical activity program is designed specifically for each individual as different people have different physical and medical problems. Do not start without seeing a GP and physiotherapist first. Programs organized by a physiotherapist should aim to achieve balance, mobility and strength and include strategies to improve confidence in mobility. Programs should be introduced gradually and should occur at a time of the day where fatigue and effects of medication are at their lowest. Avoiding back-flexion exercoses and flexed postures may help prevent vertebral fractures.

Education concerning minimizing the risk of falls and assessment regarding home hazards, illness, medications, and the need for a walking aid should all be part of the program.

A home assessment performed by a qualified occupational therapist can provide invaluable advice regarding risk reduction around the home e.g. lighting, hand-rails, floor coverings. These can be arranged through the local community health centre or through a GP and the consultation is usually free of charge (to those eligible).

Tips regarding avoiding falls outdoors

(Adapted from publications from the National Ageing Research Group.)

Most outdoor falls happen on uneven surfaces, wet floors, curbs and steps, and commonly occur when bending or turning or in the dark. The following practical tips are useful in minimising these dangers.

- Use appropriate walking aids if needed

- Use glasses if needed and, on sunny days, sunglasses and a hat to reduce glare.

- Ensure stairs and pathways are well lit and avoid walking in the dark at night or carry a torch.

- Allow eyes to adjust to a darkened environment before proceeding.

- Avoid slippery or uneven surfaces and be aware of curbs, gutters, steps, and broken paving stones.

- Look ahead to help anticipate problems / obstacles and slow down when approaching them.

- Replace worn step treads and place non-slip easily-seen adhesive strips on all treads

- Keep pathways swept and clear of obstacles, such as garden tools, toys, pets and children.

- Wear low-heeled, well-fitting shoes with a good tread.

- Consider installing stair rails

Tips regarding avoiding falls indoors

(Adapted from publications from the National Ageing Research Group.)

- Flooring

- All flooring needs to be dry and not heavily waxed or slippery.

- Ensure there is no loose carpet and fix rugs with non-skid backing.

- Lighting

- Avoid dim lighting in the home.

- Install movement sensitive lights near stairs and in the bathroom.

- Stairs

- Ensure stairs are in good repair, place non-slip easily-seen adhesive strips on all treads stairs, and ensure stairs are lit with switches at the top and bottom.

- Bathroom

- In the bathroom, use rubber mats on the floor and in the shower and the bath.

- Avoid door locks in bathrooms and toilets and place a seat in the bathroom if needed.

- Medicine cabinets should be well lit with drugs clearly labelled.

- Place hand-rails near the toilet and the shower to help with balance when getting out of shower or off the toilet.

- Kitchen

- Place a rubber mat near the sink and wear rubber soled shoes.

- Store frequently used objects at waist height to avoid bending and avoid tripod or pedestal style tables or stools.

- House in general

- Use appropriate walking aids if needed

- Be aware of any children’s toys, shoes left on the ground, and grandchildren or pets playing.

- Avoid moving furniture into positions that may cause obstructions.

- Ensure the pathway to the toilet is unobstructed.

- All furniture should be in good repair. An ideal chair should allow feet to reach the floor with knees at 90 degrees.

- Avoid chairs with wheels.

Hip protection

Special hip protectors are available to help prevent hip fracture when falls occur. They are useful in high risk patients and are available from:

- Hornsby Comfy Hips (Ph: 02 9653 3840)

- Safehip-Abena-Sanicare, St Leonards, Sydney (Ph: 1800 665 152)

- Hipsaver Qld (Ph: 1300 767 888)

- Pelical Manufacturing WA (Ph: 1800 641 577)

Further information

Osteoporosis Australia

National ageing research center

Ph 03 8387 2148

NeuRA - Falls and Balance Reference Group

https://www.neura.edu.au/research-clinic/fbrg/

This group provides a fall assessment tool for use by GPs. It takes about 10 minutes to do and is available from the web site below.